In 1848, congress appropriated $10,000 to provide a system of "surf-boats,

rockets, carronades and other necessary apparatus for the better preservation

of life and property from ship wrecks on the coast of New Jersey." At the

same time the Massachusetts Humane Society received federal funds for its stations.

The U.S. Revenue Marine was given the duty of oversight.

The

system worked poorly. Often the equipment was in place during an emergency,

but no one thought to use it. After a storm in 1854 killed many sailors

along the east coast inspectors found that there were too few stations

and that the equipment had not been maintained. One town, the report

said, was using its surf-boat, "Alternately as a trough for mixing

mortar and a tub for scalding hogs."

Congress

ordered a full-time keeper for each station and several superintendents.

But the keeper still needed to round up a crew in time of need. The

system limped along, neglected during the Civil War, neglected after

the war, neglected until the great storm of 1870, which killed so many

sailors that the newspapers clamored for reform.

In 1871,

Sumner Increase Kimball, a young lawyer from Maine, was made the chief

of the Treasury Department's Revenue Marine Division. Kimbell ordered

an immediate overhaul of the lifesaving system. Henceforth there were

to be crews of paid surfmen wherever they were needed, and for as long

as they were needed. Boats were standardized. Regulations, station

routines, and performance standards were established. There were even

physical standards to be met.

By 1875,

the network extended from Maine to Florida. In 1878, the service was

organized as a separate agency of the Treasury Department and named

the U.S. Life-Saving Service. Kimbell became General Superintendent,

and stayed there until 1914.

The Service was composed of three types of stations. Lifesaving Stations were

set up at need, usually during the winter, sometimes year-round, and consisted

of a 700 or 1000-pound surf-boat, a Lyle gun and breeches buoy for firing a

line out to a stranded vessel and hauling victims ashore, hand-drawn carts

for the transport along the beach of the aforementioned, and a gung-ho crew.

Surfmen

also patrolled remote beaches day and night in all weather. In 1899

alone, surfmen with Coston flares warned off 143 ships in danger

of running aground.

In October of that year, North Carolina surfman Rasmus Midgett came

upon a ship rapidly disintegrating on an offshore bar. Not having

time to assemble the remainder

of the team, Midgett singlehandedly saved the entire ten-man crew, swimming

out to the wreck again and again and bringing back one man each trip.

Joshua James, a Hull, Massachusetts surfman, saved more than 600 lives,

earning his first medal for heroism at age 23. On March 19, 1902, he

took his crew

out for practice during a storm. James drilled his men virtually every

day and in all weather. Just two days earlier most of the crew of the

Monomoy

Point Life-Saving Station had died in a rescue attempt and James understood

that

only incessant practice enabled the relatively light surf-boats to bring

home crew and victims alike.

After an hour of steering the boat in and out of rough surf he beached

the boat, climbed out and looked seaward, told his men, "The tide

is ebbing," and

fell dead at their feet. He was 75 and his crew buried him sitting at

the tiller of his beloved surf-boat.

Along the coasts of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, Houses of

Refuge were established. These had a keeper and small boat, but did

not attempt

active lifesaving measures. They were to provide succor to mariners

who managed to

reach shore in desolate areas. The last house of refuge still standing

is located at Gilbert's Bar, on Hutchinson Island near Stuart, Florida.

It's

now part

of a larger museum, and doubles as a sea turtle hatchery — still

providing refuge for another type of mariner.

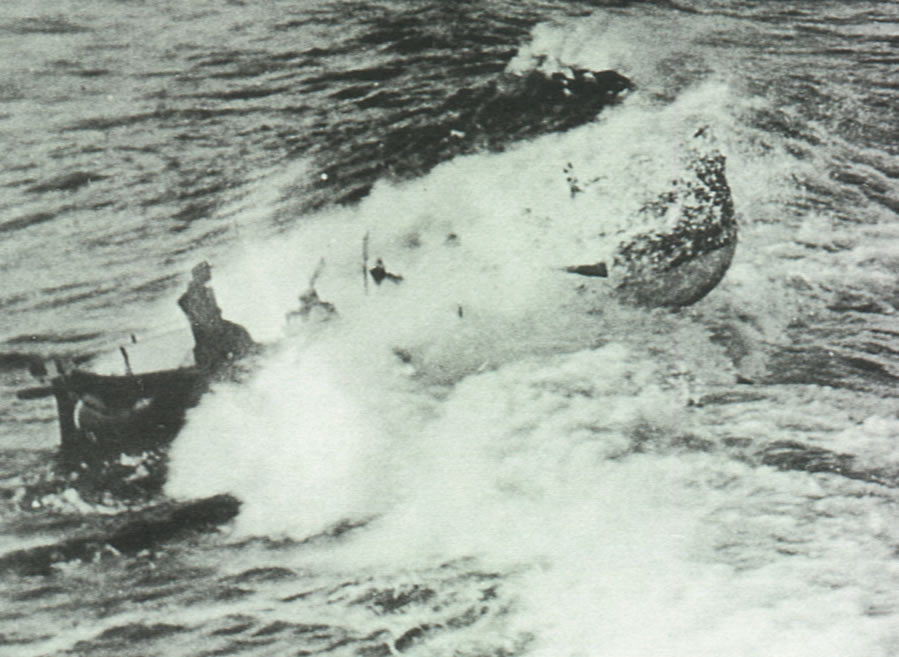

Life-boat Stations were located in or near port cities. The two-to-four-ton

life-boats were regarded by their crews with awe. Based upon a Royal

Lifeboat Society of England design, they were self-righting and self-bailing.

The

seven-man crew (six oarsmen and a tillerman) entered the boat while

it was still inside

the shed. Then someone with a mallet knocked away a restraining chock,

the boat shot down a railway and into the water, and the crew pulled

for their

lives with 12- to 18-foot oars. Practice sessions usually drew a crowd

of admiring townspeople, and rescues drew the admiration of correspondents.

" It seemed impossible for a boat to live in such a sea," wrote a witness

to the rescue of the crew of the English brig Kate Upham in 1880. "On

every hand the sea was breaking, and the life-boat, with her noble crew,

seemed but

the sport of the angry waves; one moment hidden in the trough of the sea,

the next borne rapidly on a vast comber toward the ill-fated brig. While

I could

but admire the spirit that prompted the daring men to risk their lives,

it seemed a suicidal attempt. By almost superhuman efforts they reached

the brig

and saved

the crew of eleven men."

Some attempts were suicidal; many surfmen died over the years.

But their motto, "You

have to go out; you don't have to come back," backed by rigorous

training and tough equipment, saw them through more often than not.

In 1915, Sumner Kimbell oversaw the merger of his beloved Life-Saving

Service back into the U.S. Revenue Cutter System, creating the U.S.

Coast Guard.

The Life-Saving Service had, in its forty-four years of existence,

gone to the

help of 28,121 vessels and rescued 178,741 persons. They had failed to

save just 1,455 imperiled lives, less than one percent.

In his biography of Joshua James, Sumner Kimbell described the men

of the Life-Saving Service:

"They are hardly known to their countrymen living inland; but to the inhabitants

of the coast they are well known indeed! To the latter, when the hurricane

or the chilling winter storm is driving their helpless craft into danger

and possible

destruction, or when the fog envelopes them for days at a time, the assurance

that a practically continuous line of keen-eyed and sleepless sentinels

march and countermarch along the surf-beaten beaches or stand guard with warning

signals in hand upon the jutting cliffs, lends a comfortable sense of security."

— end — |